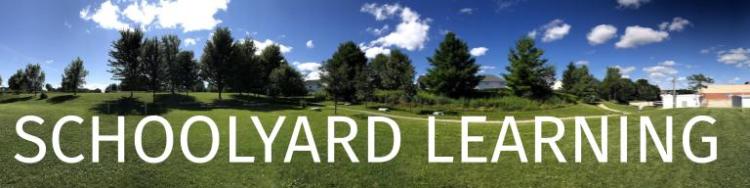

The outdoor and environmental education staff have assembled some activities for teachers looking to make use of the schoolyard with their classes. These activities require few materials and are designed to get students familiar with each other and their school grounds. There are ways that the activities may be connected with curricula, but the main purpose of them is to get classes outside and hopefully inspire teachers to see the potential of the schoolyard as a venue for future outdoor learning opportunities. Have fun!

Schoolyard Activities

Download a pdf of these activities here:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Outdoor and Environmental Education Department would like to see each school dedicate part of its schoolyard to ecological learning. In partnership with WRDSB Facilities Services, we are encouraging schools to take part in the Monarch Waystation program. There is no cost to you or your school other than some of your time. Together we can diversify our schoolyards, conserve nature and create spaces for enriched learning opportunities. Consider surveying your schoolyard for a suitable Monarch Waystation site. This is an excellent way to acquaint your students with the schoolyard, and consider what is required to create healthy habitats.

Going Further

The Basics:

The Waterloo Region District School Board will endeavour to design safe school grounds with an ecological focus, recognizing the importance of creating and sustaining healthy, natural school grounds that support child development and learning.

– WRDSB Environmental Values Policy

The Waterloo Region District School Board acknowledges that the schoolyard itself is an environment for learning. It is a resource for teachers to use, in the same way that teachers can utilize the library or the gym. Indeed, many schools have had dedicated outdoor classrooms constructed. Despite this, we tend not to envision the school grounds as a place where learning takes place. Instead, we see it as a place where students spend time in-between learning. However, for those teachers willing to look at the schoolyard through an educational lens, instructional opportunities abound.

Reasons for taking your lessons outside:

Research has found that outdoor learning has benefits for students of all ages. By doing activities outside that would normally take place in the classroom, teachers can improve students’ academic achievement, and increase their enthusiasm for the subjects being taught. Other benefits for students include greater self-confidence, increased independence, and improved problem-solving skills. The positive impacts that being outside has on physical health are well-documented, but during these uncertain times, it may be the mental health benefits of outdoor activities that motivate more educators to teach outside.

Here are some key research findings:

- Children with symptoms of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are better able to concentrate after contact with nature (Faber Taylor et al. 2001).

- Children with views of, and contact with nature score higher on tests of concentration and self-discipline. (Faber Taylor et al. 2002, Wells 2000).

- In Leiberman and Hood’s 1998 report “Closing the Achievement Gap” the authors describe how 92% of students engaged in outdoor learning outperformed their peers in several subject areas including English, math and social sciences. In his 2013 literature review Leiberman found this conclusion to be strongly supported 15 years later.

- Exposure to natural environments improves children’s cognitive development by improving their awareness, reasoning and observational skills (Pyle 2002).

- Nature buffers the impact of life stress on children and helps them deal with adversity. (Wells 2003).

- Play in a diverse natural environment reduces or eliminates anti-social behavior such as violence, bullying, vandalism and littering, as well reduces absenteeism (Coffey 2001, Malone & Tranter 2003, Moore & Cosco 2000).

- Nature helps children develop powers of observation and creativity and instills a sense of peace and being at one with the world (Crain 2001).

- Children who play in nature have more positive feelings about each other (Moore 1996).

- Natural environments stimulate social interaction between children (Moore 1986, Bixler, Floyd & Hammutt 2002).

- Outdoor environments are important to children’s development of independence and autonomy (Bartlett 1996), (White Hutchinson Leisure & Learning Group, 2004)

Overcoming barriers to going outside – Practical Concerns

Many teachers are discouraged from taking classes outside due to concerns about risk, lack of resources, and the perceived amount of preparation required. “We don’t have an outdoor classroom.” “My students won’t be dressed properly.” “I’ll need to get permission forms signed.” etc.

Taking students outdoors is a process requiring preparation, but if you are willing to make the schoolyard an extension of the classroom, the practice of going outside will become smoother, and your students will learn what is required from them to make it happen.

The first step in the process is to get clarification from your administrator as to where you can go, and what types of activities your class can engage in. Gaining a clear understanding of the physical boundaries and necessary administrative requirements from a principal can go a long way to alleviating concerns about what is feasible.

You will need to communicate your academic and behavioural expectations to students, as initially, they may not view the playground as an arena for learning. What you will probably find though, is that your students are excited about the opportunity to learn outside, and will cooperate to make it happen. Certainly, there will be extra details to attend to, such as finding an extra coat for a student, or remembering to bring extra pencils along, but having done it once, many teachers realize that many of their initial concerns were unfounded.

Overcoming barriers to going outside – Pedagogical Concerns

Many teachers think that because they have no formal training in teaching outdoors and do not have a background in natural history, that the schoolyard experience for students will have little value. This concern can be addressed in two ways.

Firstly, if the subject of study is the environment, then the exercise of going outside can be framed as a process of inquiry. “Let’s try to figure out what species of trees we have in our schoolyard.” The teacher is engaged in the process of discovery as much as the children, and modeling curiosity can help to drive the inquiry further. Even if the teacher were an expert in tree identification, this investigative approach conveys a subtle but powerful message: We’re in this together.

Secondly, the subject of study for an outdoor lesson does not need to be the environment. Many simple activities that happen in the classroom can be done outdoors. Reading, writing, math, art, and everyday class discussions can all occur outside. For teachers wondering whether it is worth the hassle of going into the schoolyard to do a lesson that can be done in the classroom, the research is pretty clear. Student engagement in the activity will be greater outside, regardless of the topic. As an added bonus, a recent study found that students who had received an outdoor lesson were able to better focus on indoor classroom instruction than their peers who were taught entirely indoors (Kuo, Browning & Penner 2018). Just going outside improves what happens inside.

Since the value of doing educational activities outside manifests itself in so many different areas, teachers may want to ask themselves, “Is there any aspect of this lesson which prevents me from teaching it outdoors?”

To help address teacher pedagogical concerns we have compiled resources for teachers on the following topics: Continuum of Teaching, Literacy Outdoors, Numeracy Outdoors, and Assessment and Documentation Outdoors.

During COVID-19

There is no research yet that describes the relative risk of contracting COVID-19 indoors versus outdoors. Guidance from Waterloo Public Health, the province of Ontario and medical experts from around the world has emphasized the importance of physical distancing. For some activities, maintaining six feet between students can be challenging, and a larger outdoor venue may be more appropriate.

Nazeem Muhajarine, professor and chair of community health and epidemiology at the University of Saskatchewan, stated that “moving classrooms outdoors in a practical sense is a safer alternative to crowded classrooms during this pandemic. There is opportunity to physically distance, have plenty of fresh air circulation, and if this option is combined with mask wearing and observing good hand-hygiene, the risk exposure to the virus can be greatly minimized.”

Suggested Resources

See WRDSB document, Design Guidelines for K-12 Outdoor Play and Learning Environments for a variety of examples. Please note that this document is currently being updated to reflect a deeper understanding of how best to use outdoor spaces at schools.